[ad_1]

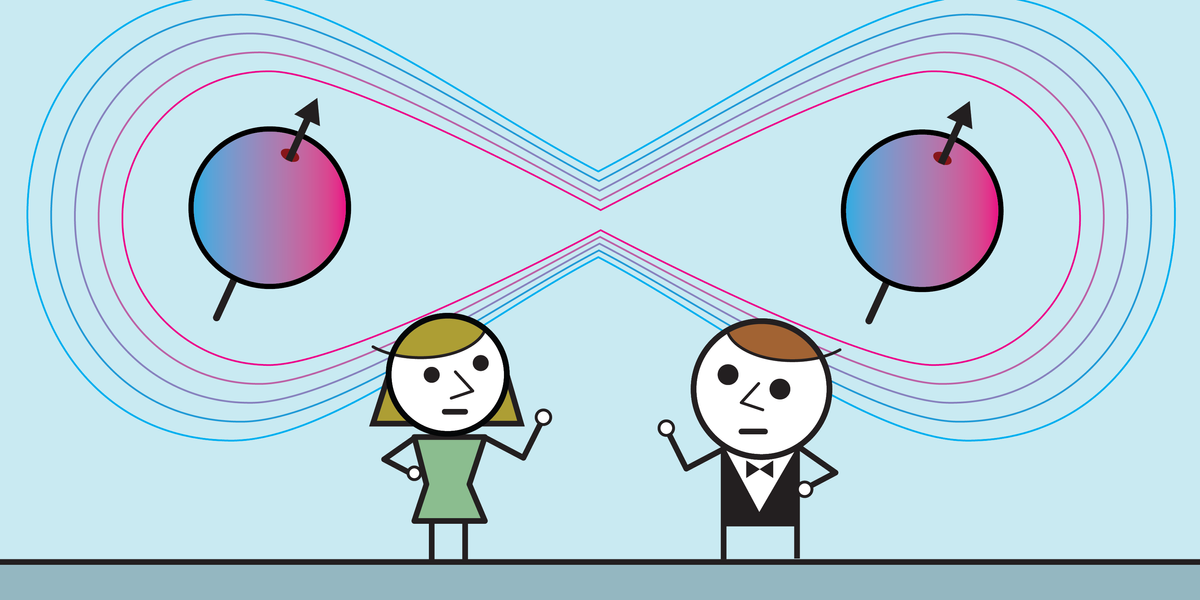

When pushed to elucidate why quantum computer systems can outspeed classical computer systems, tales about quantum computing usually invoke a mysterious property referred to as “entanglement.” Qubits, the reader is assured, can in some way be quantum mechanically

entangled such that they rely upon each other. If extra element is required, the reader is instructed that entanglement hyperlinks qubits irrespective of how far aside they’re—as long as the qubits are “coherent.”

For the reader, issues are removed from coherent. Positive, entanglement is a crucial side of quantum computing. However what precisely is it?

In a number of phrases,

entanglement is when a number of objects—comparable to a pair of electrons or photons—share a single quantum state. Like threads in a tangle of yarn, entangled objects can’t be described as impartial entities.

That clarification could be poetic, nevertheless it shouldn’t be satisfying. Issues will not be so easy or concrete. However with somewhat little bit of high-school-level math (close to the tip of this story), our intuitions—based mostly on a lifetime of classical physics—could be retrained and redirected only a bit.

Nevertheless, we also needs to make the next disclaimer: No transient clarification could be anticipated to convey a complete understanding of quantum mechanics. Our aim is just for example the essential ideas behind entanglement, so the reader can acquire a extra thorough understanding of what’s really occurring on this foundational phenomenon behind quantum computing.

Let’s start with a barely modified instance from the celebrated Northern Irish physicist

John Stewart Bell:

Alice and Bob know that Prof. Bertlmann all the time wears mismatched socks. If his left sock is pink, his proper sock is definite to not be pink. (Our illustrations are loosely based mostly on Bell’s personal cartoons of his buddy, Reinhold Bertlmann, which he drew for a

1981 article to elucidate entanglement.)

Meet Professor Bertlmann, together with his predictably and reliably mismatched socks.Mark Montgomery

Alice and Bob want to take a look at if Prof. Bertlmann’s selection in socks persists exterior the classroom, in order that they resolve to spy on him.

Suppose Alice is standing one block away, and he or she sees that Prof. Bertlmann’s left sock is blue. Instantly, she is aware of that Bob—who’s maintaining a tally of Bertlmann’s proper sock—will see pink. This holds true even when Alice is light-years away from Bertlmann, following all of the sartorial goings-on with a telescope. As soon as she measures the colour of 1 sock, Alice instantaneously is aware of one thing about what Bob will measure in regards to the different sock. It is because the pair of mismatched socks are what physicists (and overqualified wardrobe consultants) describe as being

correlated with each other.

Alice sees that Prof. Bertlmann’s proper sock is blue; Bob can see that his left sock is pink. Mark Montgomery

There isn’t a thriller to how this correlation arises: Each morning, Prof. Bertlmann deliberately mismatches his socks. If his left sock is blue, he’ll pull on a proper sock that’s pink. These correlations have three classical traits: They’re

actual, native, and deterministic.

Actual: The socks have a particular colour previous to Alice’s or Bob’s measurement.

Deterministic: The colour of the socks just isn’t random. Given precisely the identical preliminary circumstances (for instance, Tuesday, probability of rain, sore toe), Prof. Bertlmann will placed on the mismatched socks the identical means. Observe: The particular colours worn on every foot could also be troublesome for Alice and Bob to foretell, however the course of just isn’t strictly random.Native: The colour of the socks relies upon solely on close by environment—that’s, what Bob sees mustn’t rely upon Alice’s measurement.

Allow us to now suppose Prof. Bertlmann needs to show his snooping college students a factor or two about entanglement. The subsequent morning, he places on a mismatched pair of

quantum socks, whose colours are entangled.

Prof. Bertlmann complicates the state of affairs by introducing quantum socks—whose colour is indeterminate till it’s been noticed. When Alice measures the left sock, the pair’s indeterminate state of colour collapses, in order that Alice sees both pink or blue.Mark Montgomery

In contrast to his classical socks, Prof. Bertlmann’s entangled quantum socks are:

Unreal: The socks don’t have any particular colour previous to measurement.

Nondeterministic: The colour of the socks is random. Measurements underneath the very same preliminary circumstances are unpredictable—for instance, 50 p.c of the time a sock shall be pink, 50 p.c of the time will probably be blue.

Nonlocal: The colour of every sock relies on nonlocal environment—that’s, what Bob sees is dependent upon Alice’s measurement.

Within the quantum case, if Alice measures the colour of 1 sock, her measurement

instantaneously updates the colour of the opposite sock, which had beforehand been indefinite. (Observe: As a result of the sock colour is random, this doesn’t, strictly talking, transmit data—and due to this fact can’t be used for faster-than-light communication.)

However, Alice objects, the socks are shut collectively—couldn’t they ship some sign to one another? Is the replace actually instantaneous? To additional persuade his college students that there’s something nonlocal taking place, Prof. Bertlmann ships every of the socks to distant stars which are light-years other than each other. Now every of the professor’s fabled quantum socks have been despatched to totally different star techniques, many light-years aside. As earlier than, when Alice observes the left sock, the pair’s indeterminate state of colour collapses. This measurement updates the colour of the opposite sock instantaneously.For simplicity, we’ve proven solely Alice measuring, however the outcomes don’t change if Bob measures too.Mark MontgomeryThen he asks Alice and Bob to carry out the identical experiment.

Once more, what Bob sees is dependent upon Alice’s measurement, regardless that there isn’t a means for the socks to speak. This consequence ought to be stunning. As Prof. Bertlmann places it:

“How come they all the time select totally different colours when they’re checked out? How does the second sock know what the primary has executed?”

§

A short historic detour: Nervousness about entanglement originates from the well-known

1935 EPR paper by Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen (collectively often known as EPR, from their initials). EPR acknowledged that quantum mechanics specified a world that was nondeterministic and nonlocal, and argued that these properties implied that quantum mechanics is incomplete as a concept. Einstein was significantly involved in regards to the lack of locality. He famously lamented the instantaneous measurement replace between entangled particles as “spukhafte Fernwirkung” (“spooky motion at a distance”) as a result of he couldn’t reconcile it with the “concepts of physics.” From Einstein’s letters to Max Born:“If one asks what… is attribute of the world of concepts of physics, one is to begin with struck by the next: the ideas of physics relate to an actual exterior world… it’s a additional attribute of those bodily objects that they’re organized in a space-time continuum. A necessary side of this association of issues in physics is that they lay declare, at a sure time, to an existence impartial of each other.”

To protect these cheap assumptions—and rescue physics from the seemingly irreconcilable weirdness that quantum mechanics launched—physicists started enjoying with “hidden-variable theories.”

In line with hidden-variable concept, in Alice and Bob’s experiment the quantum socks are secretly predetermined (by a “hidden” variable) to be one colour or one other, and it solely

appears as if Alice’s measurement of the primary sock instantaneously updates the colour of the opposite sock. Hidden-variable theories, it was thought, might reproduce all of the odd outcomes quantum mechanics predicted with out sacrificing native realism.

Right here is the place we return to the subject of this text—as a result of quantum entanglement lies on the coronary heart of questions on hidden-variable concept.

If hidden-variable theories are right, entanglement is simply an phantasm of nonlocality; Bertlmann’s quantum socks wouldn’t in that case even have an odd connection no matter distance. But when hidden-variable theories are incorrect, entanglement actually does hyperlink the socks irrespective of how far aside they’re.

With none means of experimentally differentiating between

both concept, physicists relegated the conundrum to the realm of philosophy—till Bell, the Northern Irish physicist referenced earlier, discovered an answer.

§

Again to the current day, the place the skeptical college students Alice and Bob are unimpressed by Prof. Bertlmann’s supposedly entangled socks. Once more, from their perspective, there may be

no experimental distinction between “spooky” socks and hidden-variable socks, which solely seem to replace one another upon measurement however whose colour (based on hidden-variable concept) would really be preordained.

To enlighten his mistrustful mentees in regards to the true nature of entanglement, Prof. Bertlmann units up a brand new experiment.

On this experiment, Alice and Bob fly off in spaceships. A supply shoots out entangled pairs of quantum socks towards them. Alice and Bob every have particular detectors with two settings. Alice’s detector could be in setting A or setting a; Bob’s detector could be set to both setting B or setting b. (To select a setting, they every flip a coin after the socks are despatched so there isn’t a means the socks know the settings forward of time.)

To keep away from any attainable native results, Alice and Bob fly light-years aside. They need this isolation in order that they’ll inform if the sock colour is predetermined or actually updates upon measurement.When Alice and Bob have totally different settings (a and B, or A and b), the socks generally match and generally mismatch.When Alice and Bob share the identical settings (A and B, or a and b), the socks all the time match. How might predetermined socks handle this correlation, if the random coin flip occurred after the socks have been despatched?Mark Montgomery

Here’s a pattern output from Alice and Bob:

Alice

Bob

P

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

B

P

B

B

P

P

P

B

B

P

B

B

B

P

P

P

B

B

P

B

B

B

B

B

P

P

P

P

As you possibly can see, the colours Alice and Bob measure are random. Let’s now add the detector settings, that are additionally random.

SettingAliceSettingBob

A

P

b

B

A

B

B

B

a

B

b

B

A

B

B

B

a

B

B

P

a

B

b

B

A

P

B

P

A

P

b

B

a

P

B

P

A

B

B

B

a

B

B

P

a

P

b

P

a

B

b

B

A

P

b

B

A

B

B

B

a

B

B

B

A

P

b

P

a

P

B

P

The desk reveals that when Alice and Bob use totally different settings, the socks generally match and generally mismatch. But when Alice and Bob share a setting (each uppercase or each lowercase), they all the time match. It’s as if, although Alice and Bob flipped cash after the socks have been despatched, the socks might in some way inform one another when to match throughout the huge distance. That is very unusual—as if the sock colour have been predetermined!

After Alice and Bob have recorded all their information, they arrive again to Earth, the place Prof. Bertlmann explains that the unusual coincidence just isn’t fairly sufficient to disclose the true nature of entanglement. What they want is to measure how correlated the socks are, so Alice and Bob create a brand new desk the place pinks are -1 and blues are +1.

Setting

Alice

Setting

Bob

Mixed Setting

Sum

A

-1

b

+1

Ab

0

A

+1

B

+1

AB

2

a

+1

b

+1

ab

2

A

+1

B

+1

AB

2

a

+1

B

-1

aB

0

a

+1

b

+1

ab

2

A

-1

B

-1

AB

-2

A

-1

b

+1

Ab

0

a

-1

B

-1

aB

-2

A

+1

B

+1

AB

2

a

+1

B

-1

aB

0

a

-1

b

-1

ab

-2

a

+1

b

+1

ab

2

A

-1

b

+1

Ab

0

A

+1

B

+1

AB

2

a

+1

B

+1

aB

2

A

-1

b

-1

Ab

-2

a

-1

B

-1

aB

-2

“There’s a quite simple proof—which you could test by yourself—which states that absolutely the worth of AB – Ab + aB + ab can’t be better than 2 if the hidden-variable concept of sock colour have been true,” Prof. Bertlmann explains.

Counting, Alice and Bob tally up their measurements and discover the averages for AB, Ab, aB, and ab:

Then they plug the numbers into the components and discover that the (constructive) sum exceeds 2!

Puzzled, they ask Prof. Bertlmann what it means. He responds:

“It’s usually stated that entanglement is the essence of quantum mechanics. This straightforward mathematical inequality—that the components based mostly on the experimental outcomes will conditionally yield a solution no better than 2—is on the coronary heart of entanglement. Neither classical correlations nor the correlations of hidden-variable theories might replicate the measurements you took of my socks. Since your reply is 2.3, which is larger than 2, the one clarification is that the entanglement you measured was a essentially quantum-mechanical phenomenon. Subsequently, every pair of socks was certainly genuinely entangled. Earlier than you measured them, there was no left sock colour or proper sock colour; they have been a single quantum object.”

Whereas no socks have been entangled in the true world (but), there have been quite a few experiments confirming that quantum correlations exceed Bell’s inequality, as above. The primary experiments entangled electrons and photons, however within the many years since, scientists have even managed to entangle tiny, nanoscale objects, comparable to a pair of submicroscopic drums.

§

So, what’s entanglement? In our first definition, we stated that “entanglement is when a number of objects share a single quantum state.” We will replace that definition with what we’ve realized: Entanglement is the

quantity by which a number of objects share a quantum state. By checking the correlations of our measurements, we are able to quantify how a lot entanglement there may be between objects. The state of entangled objects can’t be described independently. Prof. Bertlmann’s quantum socks, light-years aside, will not be reducible to a left sock colour and a proper sock colour. They continue to be a pair of indeterminate colour till they’re disentangled by a measurement.

In a quantum laptop, qubits are separated by millimeters, not light-years. However the precept nonetheless holds, so an entangled pair actually is one quantum object—at the very least till Alice or Bob takes a measurement.

From Your Website ArticlesRelated Articles Across the Net

[ad_2]