[ad_1]

Eastern European Cold War–era computing has a poor reputation. The picture is one of a landscape littered with uninspired attempts to copy American IBM PCs, British ZX Spectrums, and other Western computers. But then there was Yugoslavia’s Galaksija, a very inspired bid to put a computer into the hands of regular comrades.

The

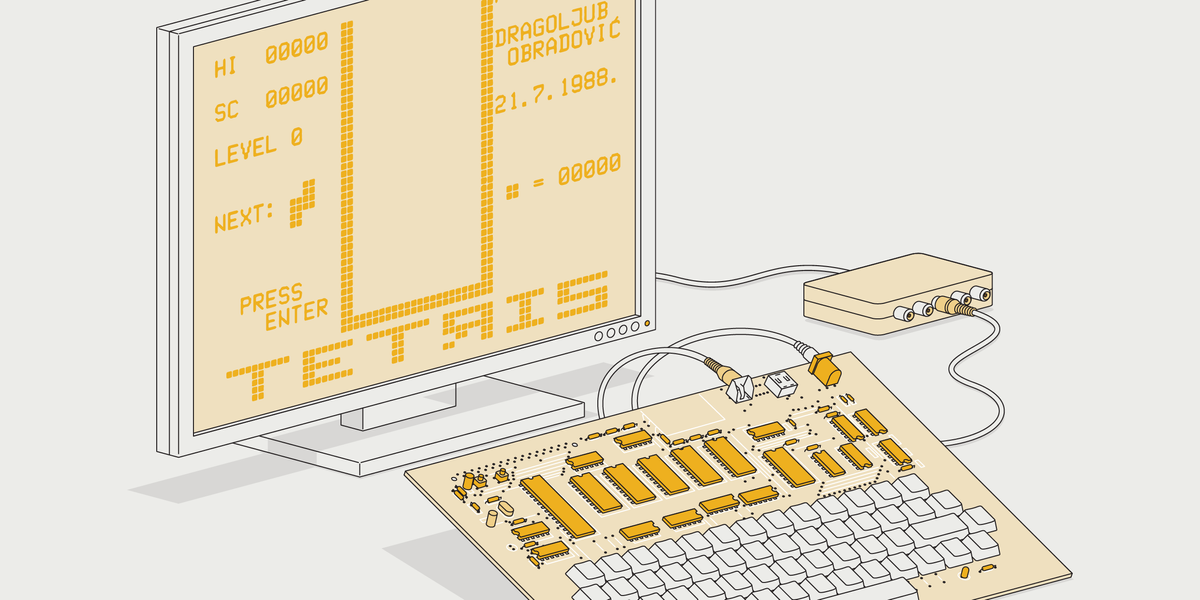

Galaksija is a Z80-based, 8-bit DIY machine, cleverly designed so that its bill of materials meshed exactly with what a Yugoslavian was able to import from Western Europe. During its brief heyday, thousands were built, leading to commercially assembled Galaksijas finding their way into homes and schools across the country. And now you can try this scrappy machine for yourself.

As a retrocomputing nerd, when I saw early last year that the Galaksija was being reissued as a complete kit through

Crowd Supply, I placed an order on general principles. But my interest was really piqued a few months later when I attended a fascinating talk on Yugoslavian computing given by Vlado Vince at the HOPE hacker conference. As delays kept pushing the delivery of the Crowd Supply kit back into an indefinite future, I ran into Vince at the Vintage Computer Festival East last April, and he slipped me a spare Galaksija printed circuit board and a link to his modern bill of materials. Figuring it was plain sailing from there, I canceled my Crowd Supply kit order and set off on my own.

Complete plans for the Galaksija were first published in 1983 in an article in the computer magazine

Računari u vašoj kući as a joint venture between the Galaksija’s designer, Voja Antonić, and the magazine’s editor, Dejan Ristanović. (An English translation of the article was published by No Starch Press in 2018 inPoC||GTFO Vol. 2.) Yugoslavians who didn’t want to try ordering components from overseas could order them from Antoić and Ristanović.

The Galaksija originally used a single-sided PCB, but a few years ago Antoić released a two-layer revision. This primarily eliminates the need to solder in jumper wires, speeding up construction considerably. The new version makes two other tweaks, with a new set of footprints for video and audio jacks, and an extra capacitor to fix a timing issue when using the modern variant of the Z80 CPU chip.

But even with these decadent concessions, you’ll still be getting a build experience that won’t feel like anything you’ve ever made if you’re under 50. For starters, many of the resistor values used will seem a little off. Modern designs typically revolve around the

E6 series of ohmic value multipliers—1.0, 1.5, 2.2, 3.3, 4.7, and 6.8. But you’ll need an E24 set on hand, as many of Galaksija’s resistors have multipliers like 1.8 or 6.2.

The Galaksija uses relatively few components, relying on its CPU to do a lot of the work that’s done by dedicated circuitry in other home computers. Two EPROMs (recognizable by the window that allows their silicon to be exposed to ultraviolet light for data erasure) store the operating system, while a third EPROM stores graphical character data.James Provost

Next, like some

other early home computers, the Galaksijia has minimal video circuitry, relying largely on the CPU to generate analog television signals. This helped greatly in keeping its component costs within the legal import limit, although the additional computing overhead did slow the Galaksija down significantly. The Galaksijia generates a European PAL TV signal, which I was able to use with a flat-screen monitor, thanks to the magic of my RetroTink-2X Pro, a wonderful little box that can convert many obsolete video signals to HDMI. You can also try plugging it into an old analog American CRT TV, because its pure black-and-white signal is compatible-ish with the NTSC standard, but I found this requires a forgiving TV and a very dab hand on the vertical hold control.

But the big headaches are the Galaksija’s ROMs, with three chips in two flavors. These chips are

erasable programmable ROMs, or EPROMs, which can be electronically written to, as with modern EEPROM chips. But to erase an EPROM you need to blast it with ultraviolet light for a few minutes through a little circular skylight window on top of its package.

Faced with a looming deadline, I did the only logical thing: I cheated.

I hadn’t handled an EPROM since the 1980s, and that was a broken one I was given to look at under my junior scientist microscope. I was able to source some on eBay, but soon realized that getting the chips was only step one of a complicated process. Like many makers, I use a cheap and cheerful

TL866-based ROM programmer. Out of the box, these can’t supply the higher voltage needed to program an EPROM, although there are instructions online for a hardware modification to allow this. But I was struggling to even read the chips to verify that they were blank. Was there a problem with my tool chain, or with the chips themselves? If my Galaksija failed to turn on properly, how would I know if the problem lay with the EPROMs or how I’d populated the board?

As seen in this diagram, adapted from EPROM inventor Dov Frohman’s 1971 paper for the IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits, each bit of memory is a transistor with an unconnected gate electrode [dark rectangle]. To set a bit, the gate is charged by applying a high breakdown voltage between the transistor’s source and drain, trapping electrons. The field produced by the trapped gate electrons creates a conductive layer in the silicon substrate. The gate is reset by exposing the surface to penetrating UV light.James Provost

Faced with what looked like a lengthy sequence of trial and error, and a looming deadline for this article, I did the only logical thing: I cheated. I emailed Vince, who conveniently also lives in New York City, and he volunteered to come into the

IEEE Spectrum office, along with his UV EPROM eraser, hacked TL866 programmer, and some programmed ROMs for testing. After about two hours of troubleshooting, including tossing a dud chip, my Galaksija was displaying its READY prompt. Really, everyone should have an 8-bit Yugoslavian DIY computer guy: You may not need them for years, but when you do, you’re really glad you have themYou don’t have to know Serbian or Croatian to program the Galaksija. It has a version of Basic used by the

TRS-80 Model 1, and hence English keywords. Software is saved and loaded through an audio jack originally intended to interface with tape recorders, and there are collections of Galaksija software available for download, including classics like Tetris. The Galaksija may not be as famous as Western 8-bit machines like the ZX Spectrum or Commodore 64, but getting to know it is a great way to see how people in other places joined the digital revolution and how motivated engineering can transcend major barriers.

From Your Site ArticlesRelated Articles Around the Web

[ad_2]